click the picture

17 million light-years from Earth lies Messier 64, otherwise known as the Black Eye Galaxy, or Sleeping Beauty. Discovered in 1779 by Edward Pigott, astronomers thought for centuries that it was a fairly ordinary spiral galaxy.

But recent observations, including those of the Hubble telescope, have revealed something truly extraordinary about M64. While it is true that all of the stars are rotating in the same direction, it appears that the gases in the outer regions of the galaxy are going the other way! Where the two opposite-rotating regions intersect, a vast circle of new stars can be clearly seen, shining bright blue and pink in the photo. What could be the cause of this unusual phenomenon?

Astronomers believe that perhaps a billion or so years ago, a smaller galaxy was sucked into M64. Since then, all of its stellar matter has been absorbed, leaving only the contrary rotating gases as a vestige of its existence.

click the picture

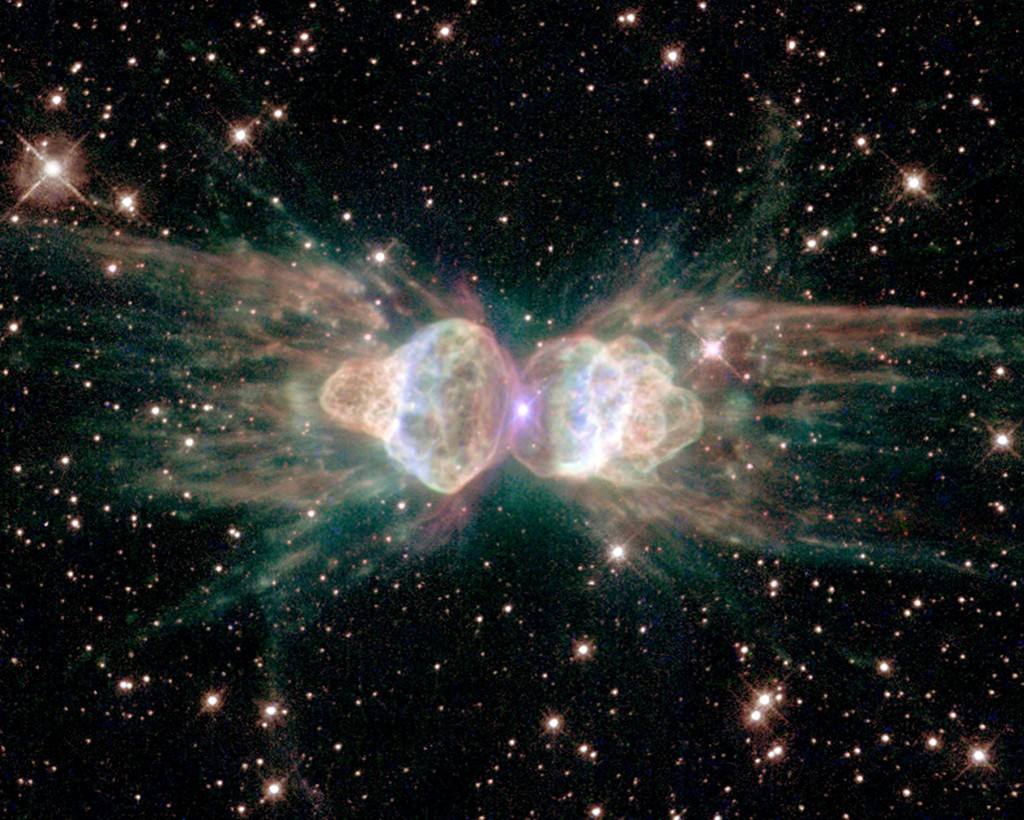

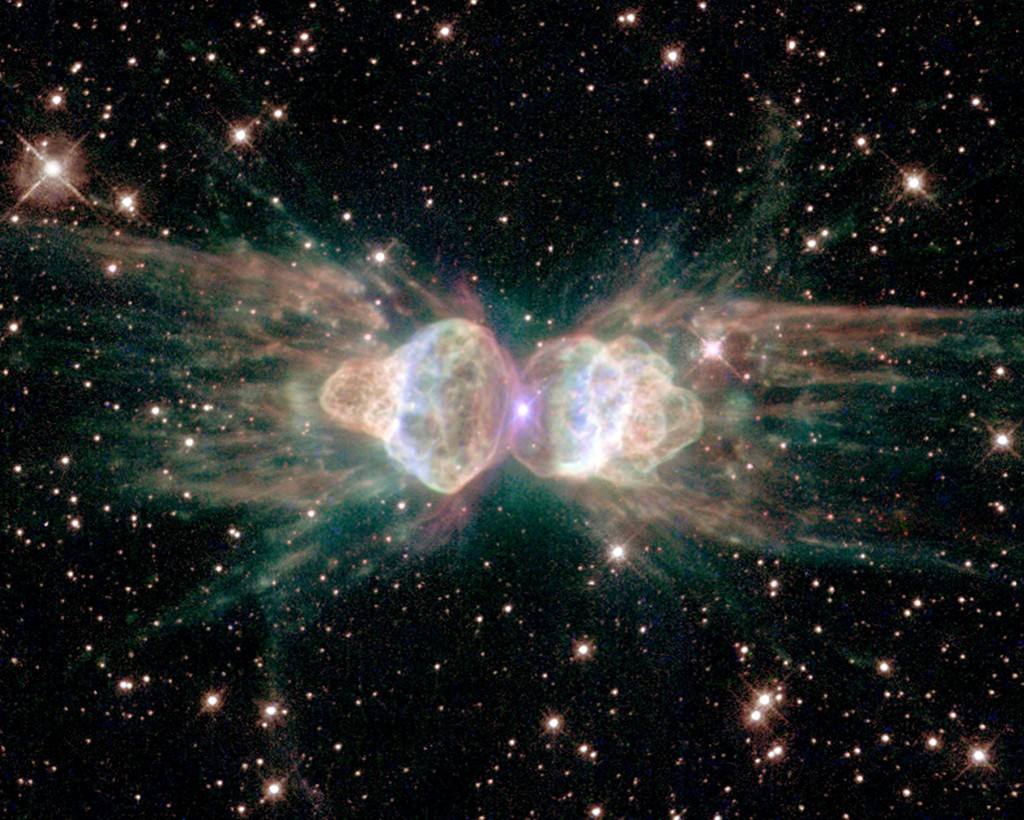

This Hubble photo of the dying star Menzel 3, popularly known as the “Ant Nebula” because of its shape, gives us a dramatic new insight into how our own sun is likely to expire: not with a whimper, but a bang.

The star at the center of the Ant Nebula has become vast in size and is ejecting gas into space in weird but symmetrical patterns, forming the body of the “ant”. These gases travel at speeds of 1000Km per second, and are millions of times more dense than the gases that comprise our own sun’s solar winds.

There are many other sunlike stars that have been observed in their death dance, but none is quite like the Ant Nebula.

click the picture

Hubble probed 230 million light years deep into the constellation Perseus to snap this visible light photo of the brilliant and spectacularly energetic constellation NGC 1275, surrounded by vast filaments of hydrogen gas, some as long as 20,000 light years, being sucked into the irresistible gravitational force of the black hole at the center of the galaxy at a rate of 3000 kilometers per second – over 6 million miles per hour.

Entire galaxies are being sucked inexorably toward the black hole, one appearing as a blurry bright spot in the lower right of the photo. The objects that look more like stars are in fact stars in our own Milky Way galaxy, thousands of times closer.

The darker material in front of the dazzling core appears to belong to another galaxy that has spiraled close enough to NGC1275 to be absorbing some of its vast energy and undergoing momentous star formation even as it plummets towards oblivion.

click the picture

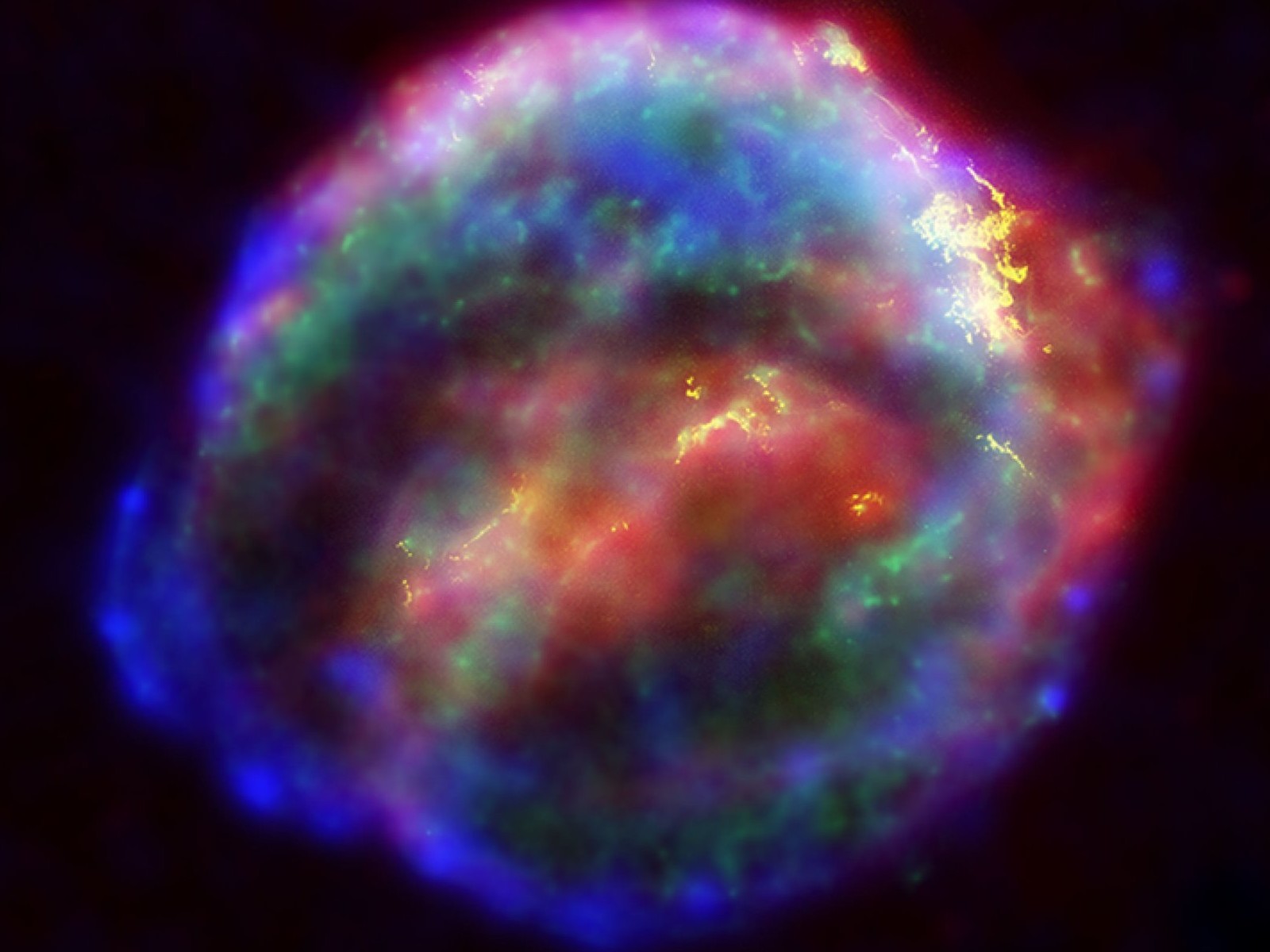

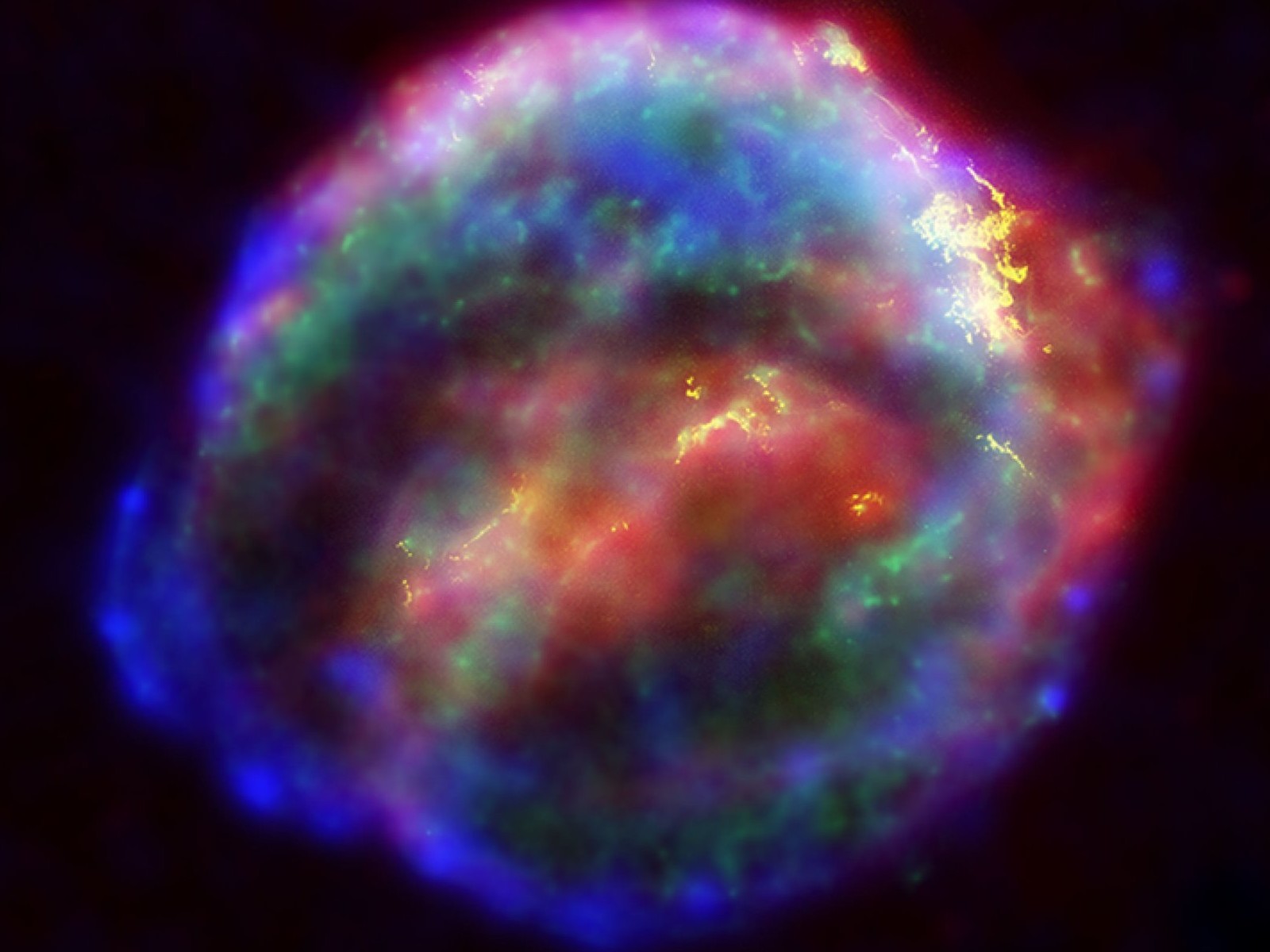

Four hundred years ago, an object in the constellation Ophiuchus (“the snake-holder”, near Sagittarius and Scorpio) suddenly lit up with an intensity greater than any other star, brighter even than Venus. Astronomers of the era, including Johannes Kepler, thought they were observing the birth of a new star.

What they were actually observing, of course, was the death of an old star, what we have come to know as a “supernova”. In this composite of photos taken by the Hubble space telescope and the terrestrial Chandra telescope, we can see the bright filaments of solid matter surrounded by a vast cloud of hot gases, invisible to the human eye, but exposed by the x-ray vision of Chandra.

The cloud of debris from Kepler’s Supernova now measures about 14 light-years across and is expanding at a rate of 4 million miles per second. At a distance of merely 13,000 light-years from Earth, Kepler’s Supernova is one of only six supernovas ever observed in our own galaxy. It is still not known whether this supernova will continue to disperse or eventually collapse into a Black Hole.

click the picture

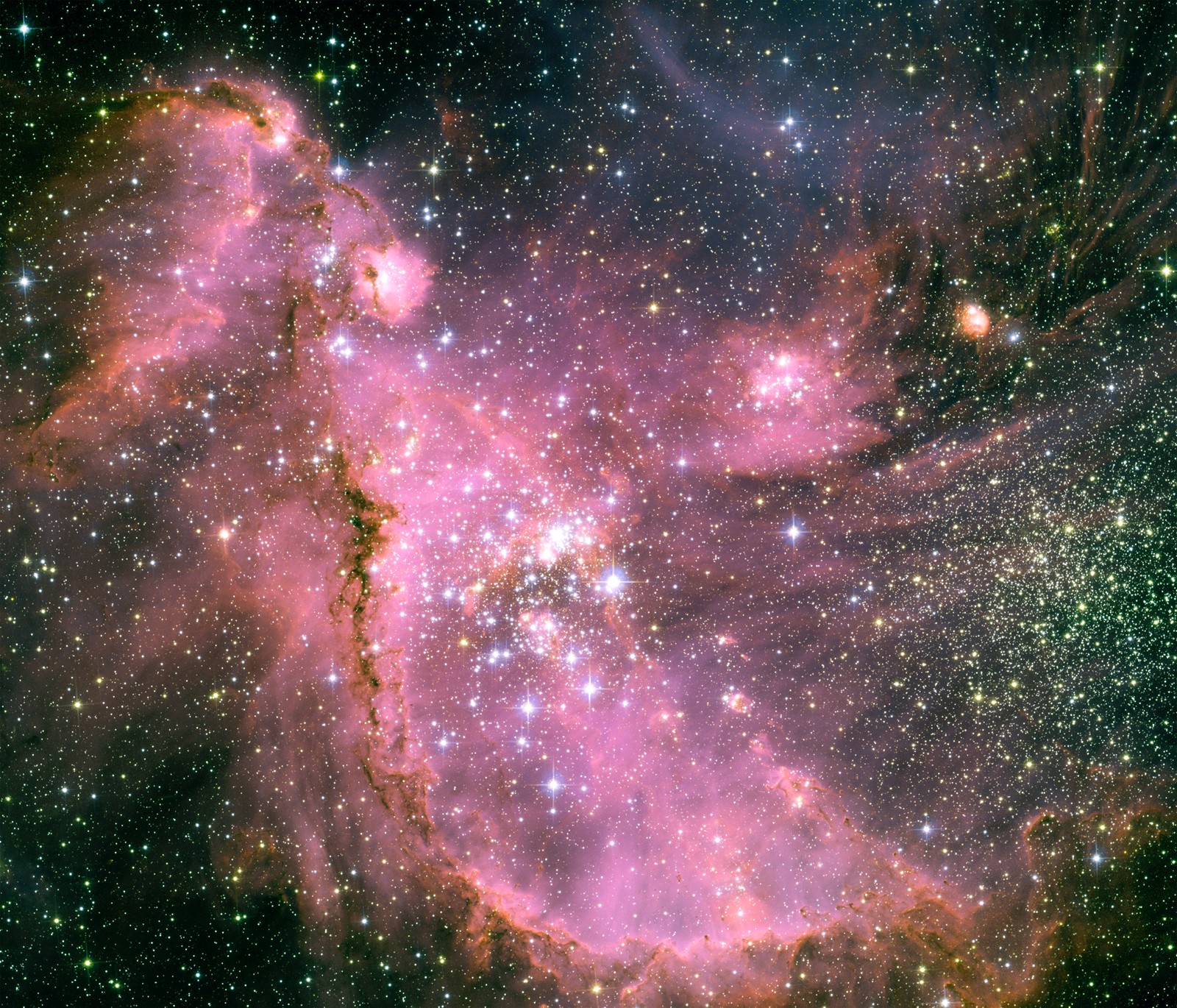

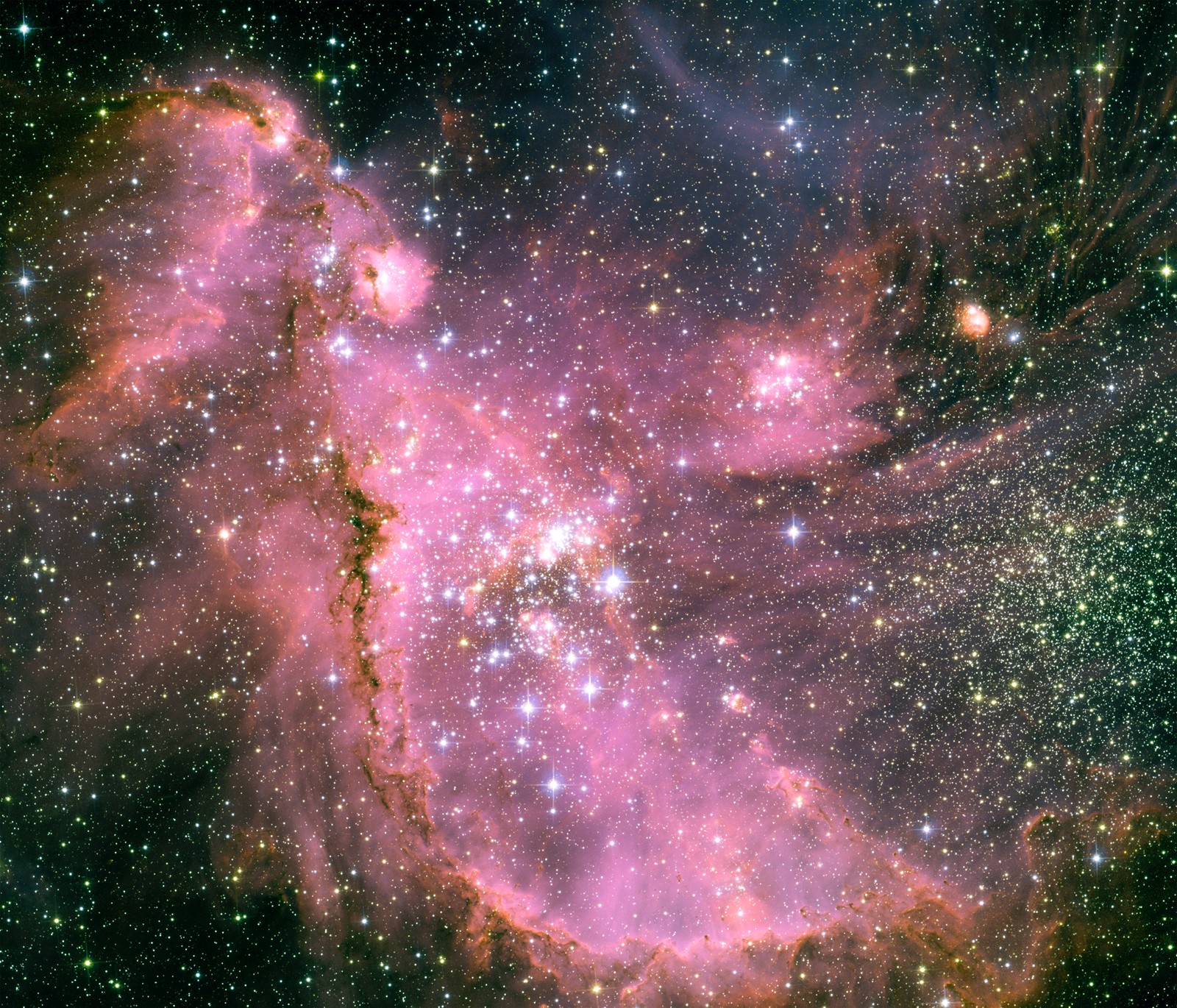

One of the most dynamic and intricately detailed star-forming regions in space is located in the Small Magellanic Cloud, a diffuse, irregular galaxy orbiting our own Milky Way, slowly succumbing to its gravitational force and an eventual union with it. At the present time, it is about 210,000 light-years away, and is visible to the naked eye from the southern hemisphere.

At the center of the region is a brilliant star cluster called NGC 346, containing dozens of hot, blue, high-mass stars, more than half of the known high-mass stars in the entire galaxy. A myriad of smaller, compact clusters is also visible throughout the region. A dramatic structure of arched, ragged filaments with a distinct ridge surrounds the cluster.

A torrent of radiation from the cluster’s hot stars eats into denser areas creating a fantasy sculpture of dust and gas. The dark, intricately beaded edge of the ridge contains several small dust globules that point back towards the central cluster, like windsocks caught in a gale.

click the picture

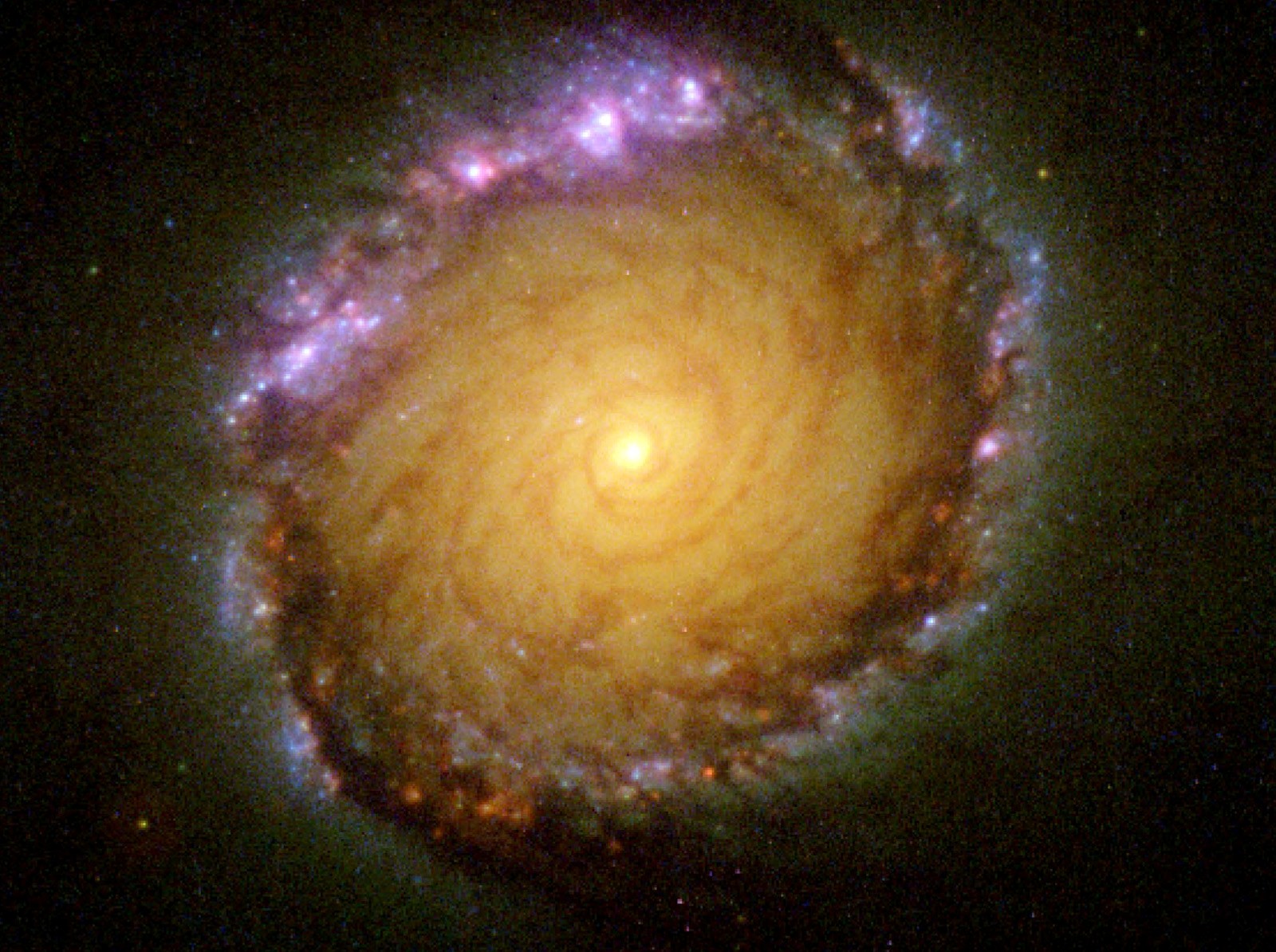

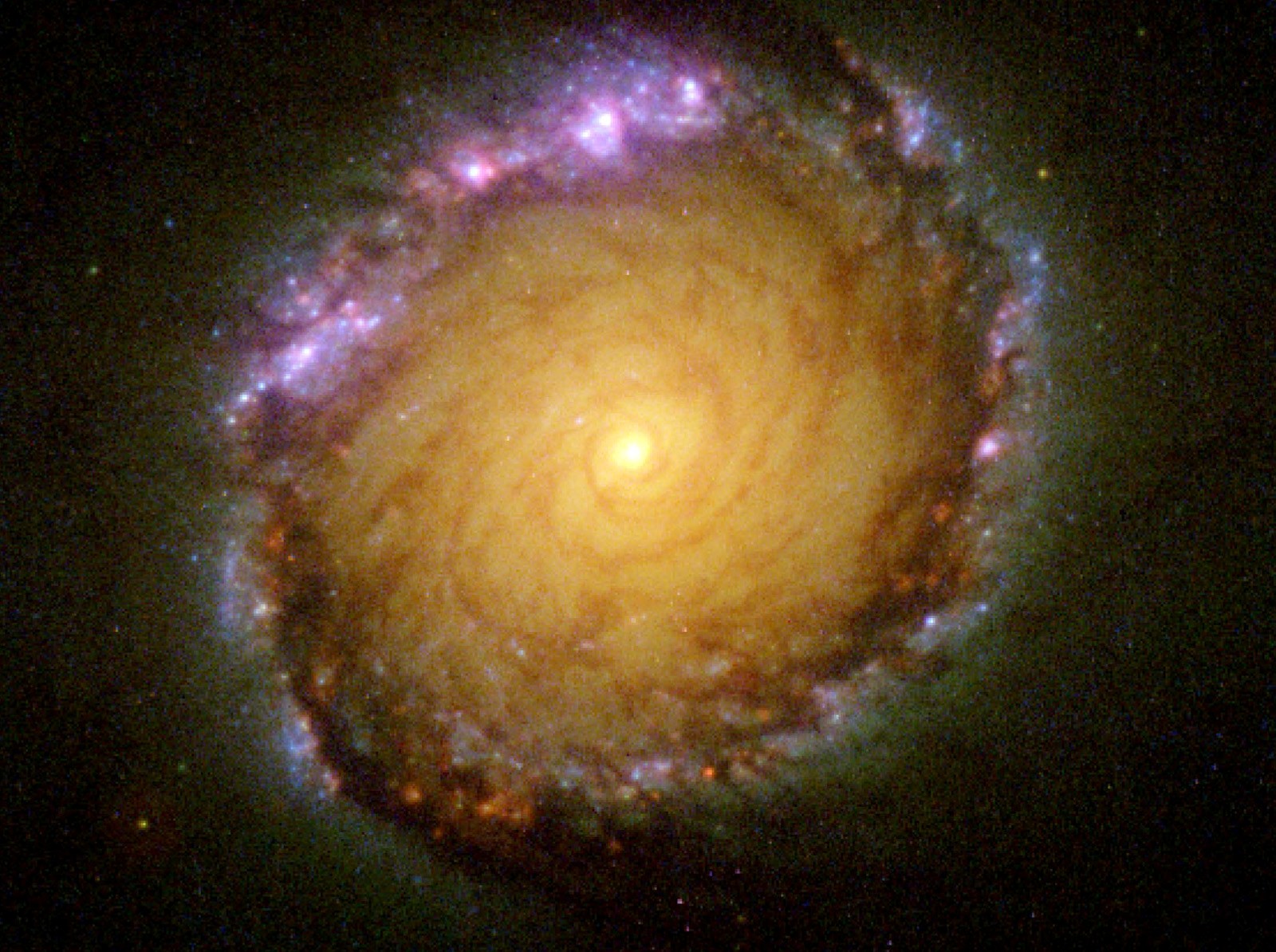

NGC 1512 is a “barred spiral” galaxy in the southern constellation of Horologium (“the clock”). Located a mere 30 million light-years away, it is bright enough to be seen with an ordinary telescope. The galaxy spans 70,000 light-years, approximately the size of our Milky Way galaxy, which is also a barred spiral galaxy.

Astronomers believe that the “bar”, which consists of a concentration of stellar gases with a more linear rather than spiral shape, forms as the galaxy stabilizes over a period of two billion years or so. They think that the gases are being sucked into the core to further fuel the frenzy of star formation.

This photo shows NGC1512’s spectacular core, comprised of a huge star foundry, or “circumnuclear starburst ring”, 2,400 light years in diameter. The dull, reddish areas around the periphery of the core are star birthing clusters that are shrouded in interstellar dust and gas. The bright blue areas are clusters that have been cleared of the usual dust and gas by powerful radiation “wind” generated by the newly formed stars.

Hidden behind a veil of interstellar dust is the densest cluster of stars in our galaxy, the Arches Cluster. Within a span of two light-years, there are some 2,000 stars, including as many as 150 stars that are close to the maximum theoretical limit of mass, beyond which a star will quickly explode into a supernova, then collapse into a Black Hole.

The Arches Cluster cannot be seen with a normal optical telescope, because of the vast clouds of dust obscuring the view, but with infrared sensors, enough information has been collected by Hubble and other, ground-based telescopes to create this artistic depiction of the cluster. It is located a mere 100 light-years from the center of our galaxy, represented by the red blotch at lower right.

The Arches Cluster is so named for the glowing arch of hydrogen filaments at upper left in this rendering, illuminated by the intense energy being generated by the massive stars. Each of the 150 largest stars emits several million times as much energy as our sun, bringing the temperature in the cluster region to a very uncomfortable 63 Million degrees.

Deep in the skies of the Southern Hemisphere is the vast Carina Nebula, a 50 light-year wide menagerie of supernova remnants, star foundries, hot and cold gas clouds, dust pillars, and other exotic stellar matter, along with one of the most massive stars in the entire universe, Eta Carina, four million times as bright as our Sun.

Just barely to the right of Eta Carina is an area known as the Keyhole Nebula, the remnants of a cosmic outburst from the colossal star. In this reverse-color image, the remaining gases glow with energy amidst the dark swathes of stellar dust. At the upper left of the photo is a huge globule that astronomers have nicknamed “the finger of God”. This feature is similar in size to our entire solar system.

The brightest supernova remnant in the Magellanic Clouds, N132D, belongs to the rare class of oxygen-rich remnants, about a dozen objects that show optical emission from pure heavy-element ejecta. They originate in explosions of massive stars that produce large amounts of oxygen, although only a tiny fraction of that oxygen is found to emit at optical wavelengths.

NGC 1309 is a spiral galaxy of unusually compact and symmetrical structure, made all the more stunning because it appears face-on from our perspective. It is about 100 Million light-years away, and only 32,000 light years across. NGC 1309 was home to supernova SN 2002fk, whose light reached Earth in September 2002.

![]()